Extreme Low-Fire glazes – Glaze Fire Ceramic In The Campfire!

Is it possible to melt a pottery glaze at temperatures as low as 550 – 600°C?

That’s campfire temperatures! Perfect for grilling hot dogs.

If you fire clay at 500 – 550°C, it will still be clay when it’s cooled down.

Can a ceramic glaze melt so low?

The answer is Yes, it’s possible!

(Ups, not tested it in an electric kiln)

Here, I’m searching for extremely low, low-fire glazes, I don’t mean smoke-fire or other techniques that just color the outer layer of the clay surface; here, I try to develop “real” ceramic (campfire) glazes that melt out and cover the pottery with a glaze layer.

Extreme Low-Fire Glazes:

For high-fire pottery, there exist many different melting agents; for extreme low-fire glazes, on the other hand, there are just a few. Not many melting agents start to flux in these low temperatures. Several of them are also water-soluble, and some are even water-soluble after they are fired into a ceramic glaze. So here I target sculptural and visually appealing glazes; food-safe? In these low temperatures, I don’t know.

Extreme low-fire glazes require an exceptionally high percentage of flux, so the cost of achieving a melt at such low temperatures, is glaze formulations dominated by one or several melting agents, which means little room for other ingredients. The small space for non-flux ingredients can turn out to be a visual limitation for extremely low-fire glazes, we’ll see. As a rule of thumb, 3-4 parts flux to 1 part non-flux ingredients seems realistic.

Glaze Fire Ceramic In The Campfire:

Extreme low-fire example glaze:

9 parts flux

2 parts Quarts

1 part “whatever you want”

Examples of extreme low-fire flux glazes:

Glaze Fire Ceramic In The Campfire:

I don’t measure the temperature for these glazes, they are campfire-glazes, and it gets as hot as it gets, that’s what I develop them for. I fire with 2-3 birch logs and put the pottery in between. And I fire it in a semi-enclosed space, to make sure cold wind doesn’t lower the temperature (picture is coming). Even though my “kiln” is not hotter than 600 °C, the flames are hotter, “dancing flames” can maybe for a short time on local spots, contribute to a much higher temperature and melt. This seems to make strong variations in many of the glazes.

I do not use Lead due to health and environmental concerns, Lead is a strong low-temp flux.

Read about the 9 essential fluxing agents here:

important-fluxing-agents-in-the-pottery-studio/

Also, read about how to bisque fire ceramic in an ordinary wood stove:

fire-ceramic-in-a-wood-stove/

Glaze Fire Ceramic In The Campfire at 600 °C. Extreme low-fire ceramic glazes:

These tests are not for making cool glazes, they’re for finding strong melts and good material combinations. Though, some are cool as-is.

Lithium dry yellow wash

XX00 – 600 °C Not much of a glaze, but I kind of liked it as a thin wash

1 part Lithium Carbonate

2 part Gersley Borate

1 part Sodium Bicarbonate (Soda Ash/Baking Soda)

1 part Sinkoxid

1 part Quarts

1 part Kaolin

1 part Iron oxid

Borax frit semi-melted glaze

XX01 – 600 °C – It starts to melt when thick, but the frit is not active enough in these low temperatures.

2 part Borax Frit P2953.1

1 part Color stains

Lithium melted glaze

XX02 – 600 °C – Now this is more like it: 4 of 5 parts in this glaze are a flux, and it starts to melt, the glaze should have been thicker.

2 part Lithium Carbonate

2 part Gerstley Borate

1 part Quarts

1 part Kaolin

1/2 part Color stains

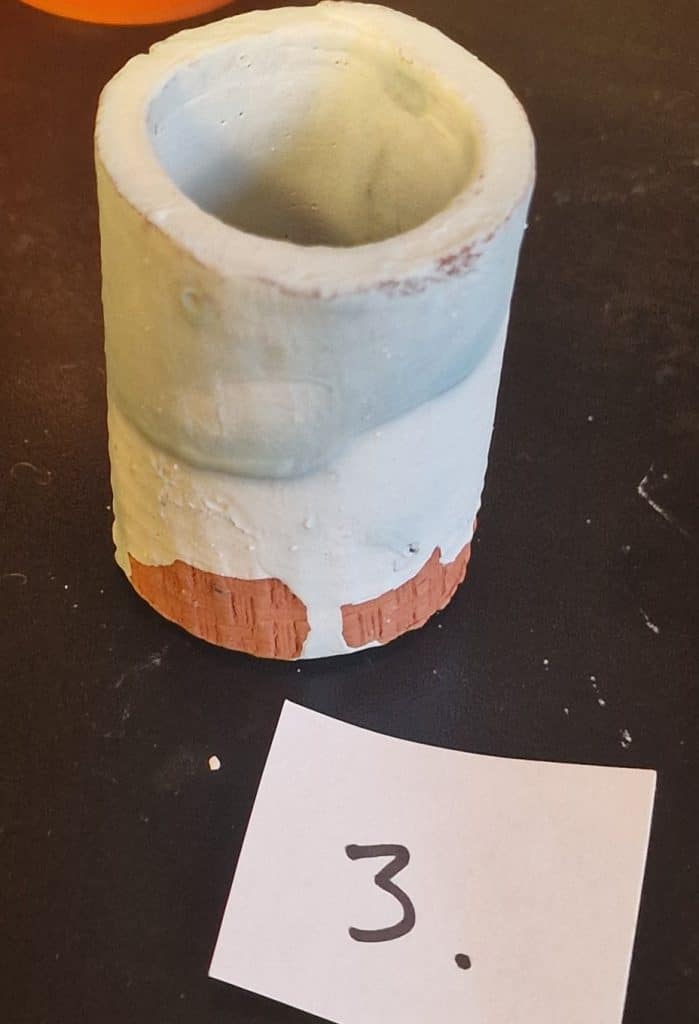

White-blue dry glaze

XX03 – 600 °C – No, Strontium did not add to the melt.

1 part Gersley Borate

1 part Lithium Carbonate

1 part Strontium Carbonate

1 part Quarts

1 part Kaolin

1/2 part Color stains

To dry wood ash glaze

XX04 – 600 °C – Did not melt; after a minute in water, it could be peeled off.

1 part Lithium Carbonate

1 part Gersley Borate

2 part Birch Wood Ash

1 part Eggshell (Calcium Carbonate alternative)

1/2 part Color stains

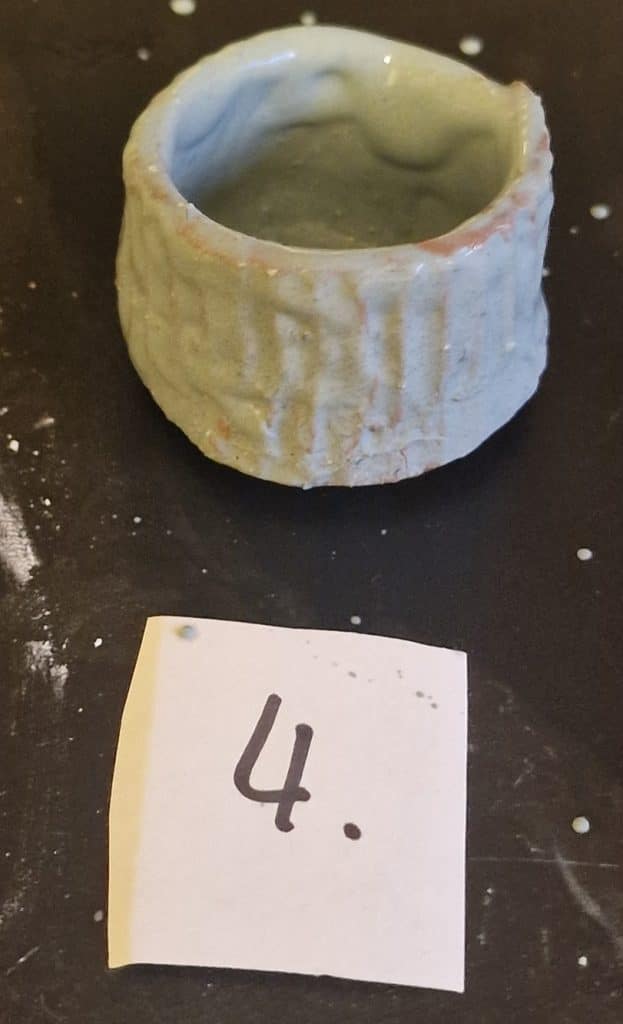

Lithium dry glaze

XX05 – 600 °C – Dry, Zink did not contribute to the melt, to little Quarts.

2 part Lithium Carbonate

1 part Gersley Borate

1 part Zink Oxide

1 part Quarts

1 part Kaolin

1/2 part Color stains

First “real” extreme low-temp glaze

XX06 – 600 °C – Melts well; this is a real low-temperature glaze! Strong color variations from green, rust, yellow, and brown. Inside, and out of reach from the flames, the glaze has not melted and can be piled off.

3 part Borax

2 part Gersley Borate

1 part Lithium Carbonate

1 part Sodium Carbonate (baking soda)

2 part Quartz

1 part Kaolin

1/4 part Copper carbonate

(mixed in Vodka mix, not water)

Lithium Borax glaze

XX07 – 600 °C – When the heat starts to build up, this glaze begins to make bubbles. That’s not a good sign, but it seems to melt and layer back again to the surface. When thick enough, it gets glossy, where the piece has been in reduction it’s metallic gray, in oxidation; red, brown, and dark. This is definitely forming a glaze. When glaze fire ceramic in the campfire, the objects will eventually fall down, and ember, coal, and ash will stick to the melt.

1 part Lithium Carbonate

1 part Borax

2 part Quarts

1 part Kaolin

1/4 part Copper carbonate

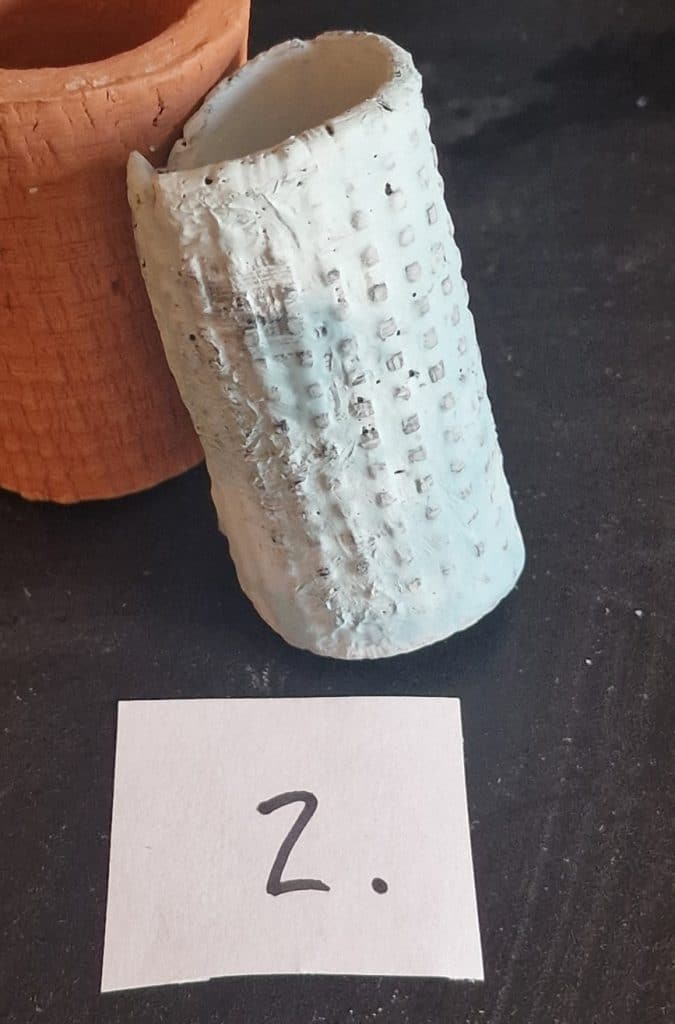

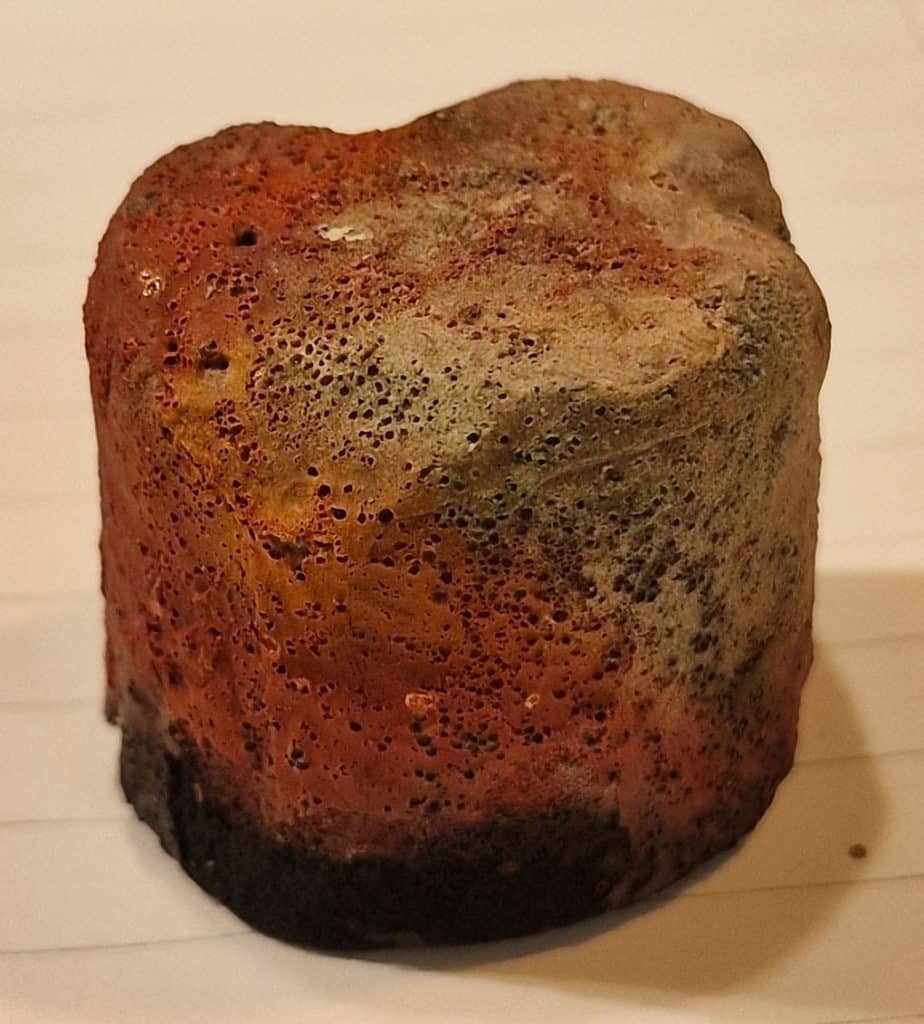

Four flux – red-brown-blue glaze

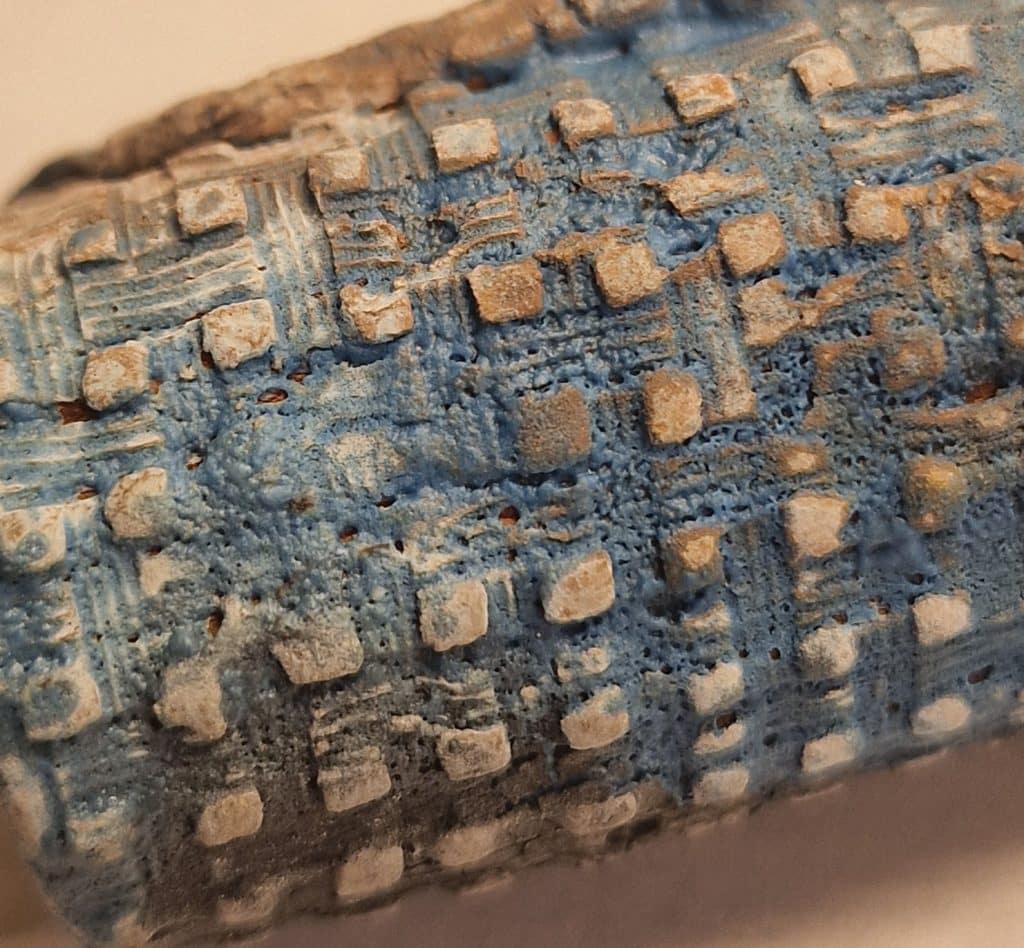

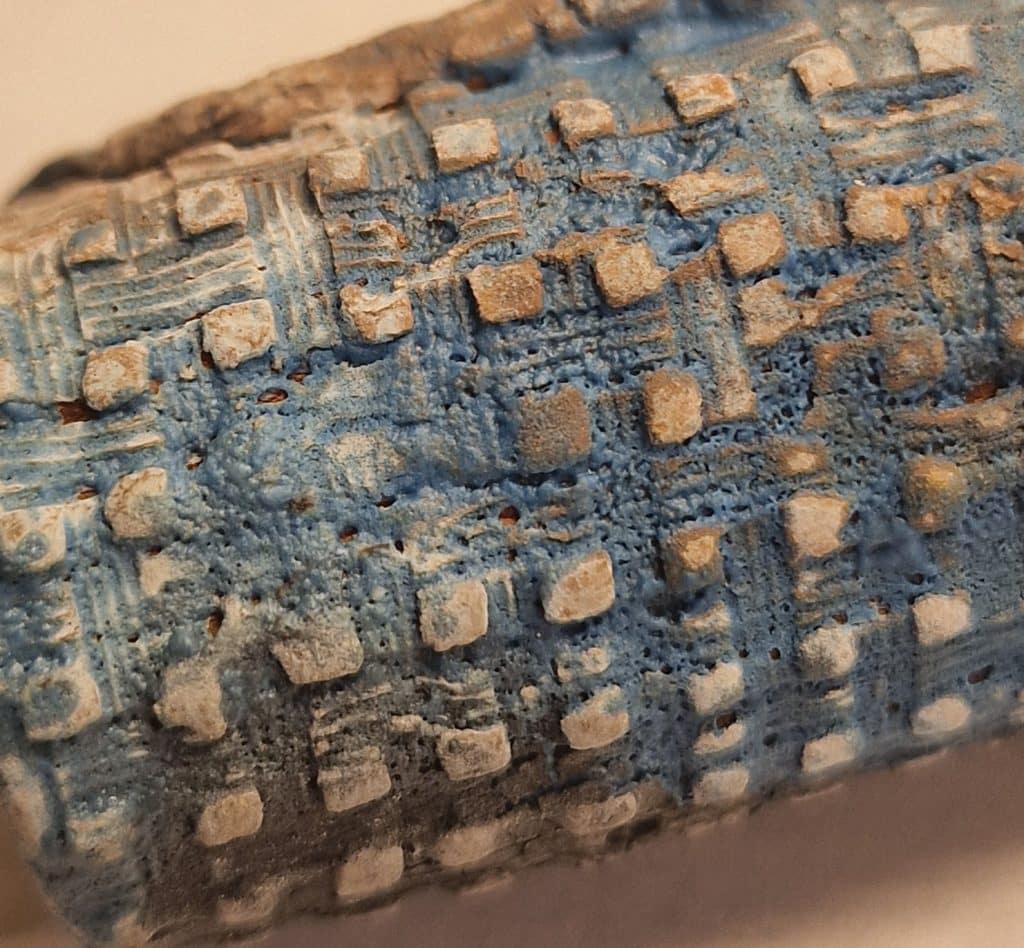

XX08 – 600 °C – When the glaze is thicker, it develops a nice blue color. The white balls are Borax; heat seems to make “crystall-balls”, if the temperature got higher they melts into the glaze, only objects in the hottest zone melted, it is possible to make a melt without Lithium in these temperatures, but it’s harder, both Gersley Borate and Colemanite raised the melting point too.

2 part Borax

2 part Gersley Borate

2 part Sodium Carbonate (baking soda)

1 part Colemanite

2 part Quarts

1 part Kaolin

1/4 part Copper carbonate

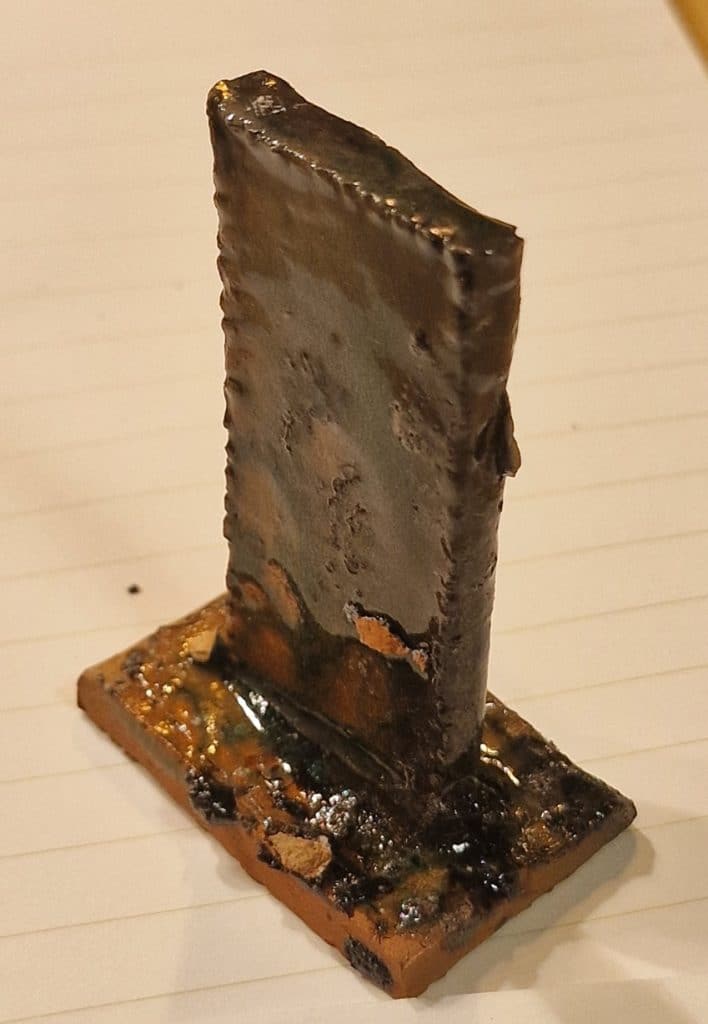

Chocolate black glaze

XX09 – 600 °C. A full-scale, extreme low-fire glaze, dark, greate, needs to have some thickness, green-blue as thin, dark brown as thick.

3 part Sodium Bicarbonate (Soda Ash/Baking Soda)

2 part Borax

1 part Lithium Carbonate

1 part Feldspar Soda

2 part Quarts

1/2 part Bentonite

1/2 part Iron Oxide Yellow

Sodium chocolate brown glaze

XX10 – 600 °C – Except for one dry area without glaze (I don’t know what happened there). The chocolate brown glaze, not too appealing when thick, has potential.

3 part Sodium bicarbonate (Soda Ash/Baking Soda)

2 part Borax

1 part Rutil

4 part Quarts

1/2 part Bentonite

1/2 part Iron Oxide Yellow

1/2 part Copper carbonate

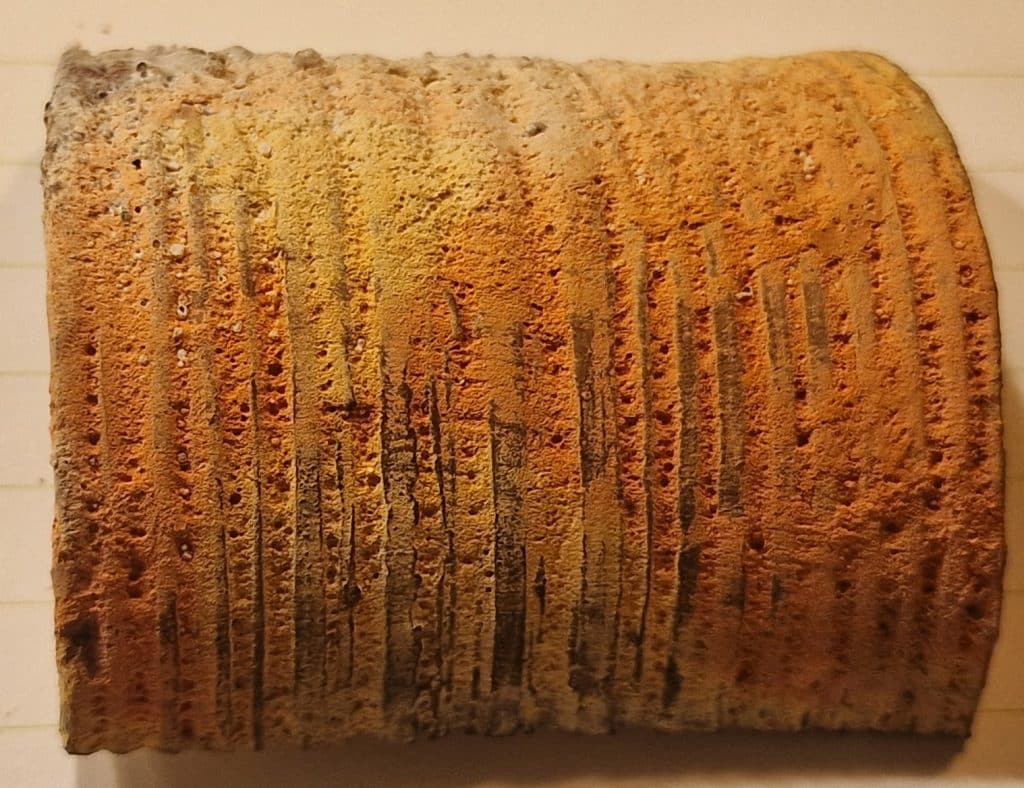

Borax and Talc – brown blue/green glaze

XX11 – 600 °C – Very distinct color differences; maybe the glaze-thickness makes the difference? The brown picks up some classic wood-fire colorations at a really low temperature. I expected the talcum to add a brighter expression.

4 part Borax

1/2 part Lithium Carbonate

1 part Talc

1/2 part Bentonite

4 part Quarts

1/2 part Copper carbonate

Pure Borax glaze

XX12 – 600 °C – This has nothing to melt except Borax, it is hardly a glaze and feels like painting with sand. Borax has a high Boron content, and Boron is a strong glass-former.

100% Borax

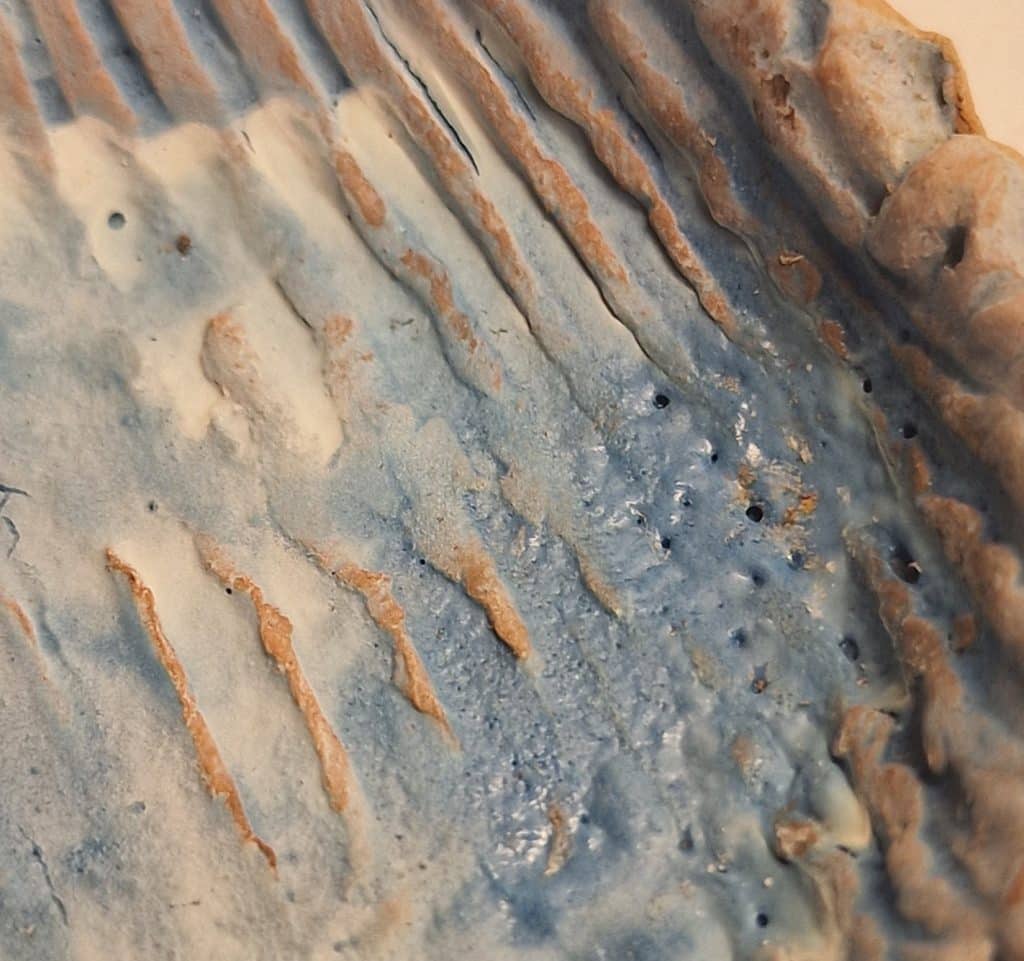

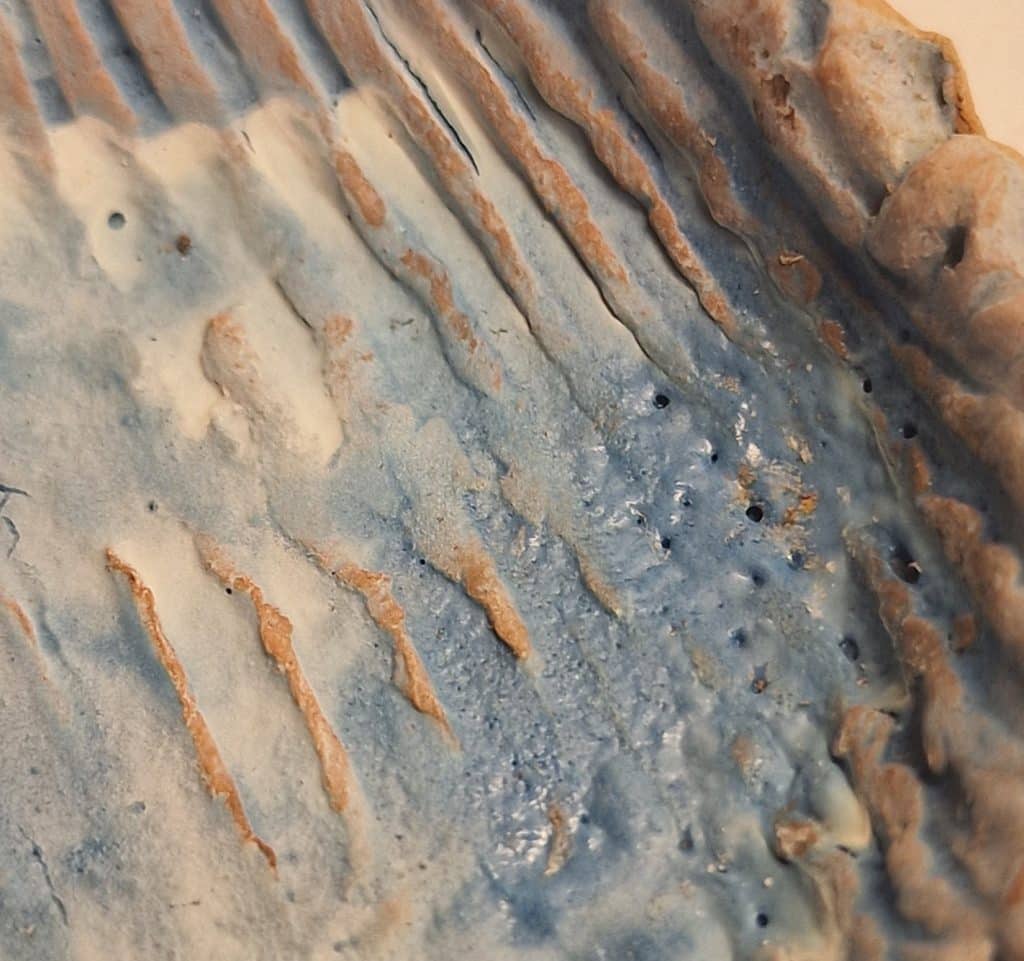

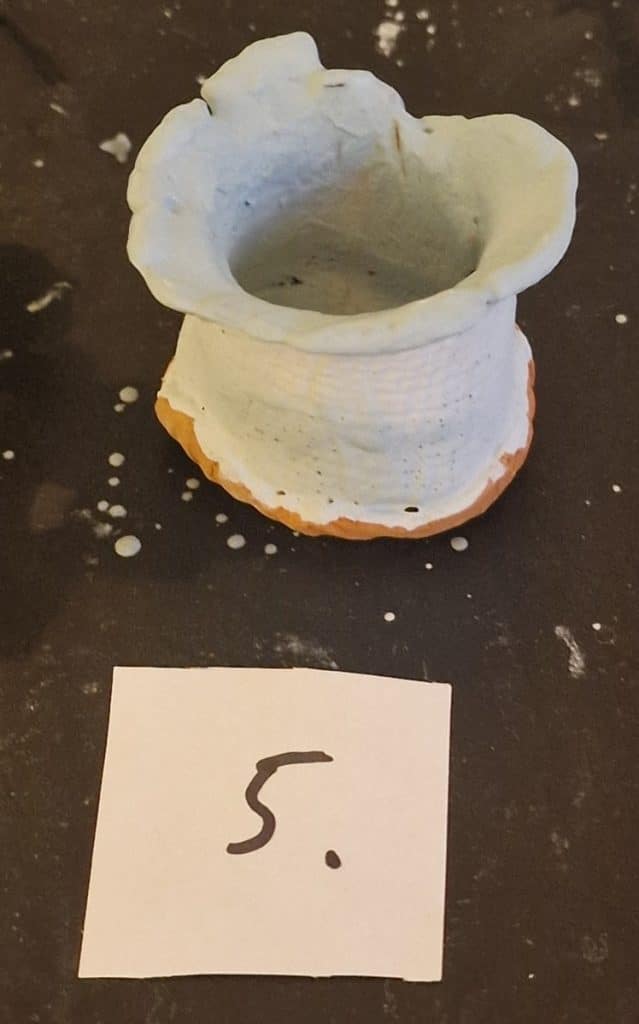

Beautiful Blue – Largely unmelted glaze

XX13 – 600 °C – Melted out in the hottest flames, but most unmelted. Looks like a great glaze with beautiful blue/yellow/brown colors, but it really needs some 50-100 degrees C extra or more flux. Sadly, adding small amounts of Talc, Magnesium, and Kaolin is enough to reduce the flux domination over its melting point.

3 part Borax

2 part Gerstley Borate

1 part Lithium Carbonate

1 part Talc

1 part Magnesium Carbonate

4 part Quarts

1 part Kaolin

1/2 part Copper carbonate

Unmelted dry glaze

XX14 – 600 °C – Not enough fluxing agents, too large amounts of other substances, too little flux. It has melted some “pearls” spotted around, maybe it’s Borax pearls?

2 part Borax

1 part Lithium Carbonate

2 part Talc

1 part Magnesium Carbonate

1 part Kaolin

3 part Quarts

1/2 part Yellow iron oxide

Strontium semi-matte hard glaze

XX15 – 600 °C – Glossy hard surface, complete melt, nice feeling. This is a good low-fire glaze.

4 part Borax

2 part Gersley Borate

1 part Lithium Carbonate

1 part Strontium

2 part Quarts

1/2 part Yellow iron oxide

Sodium Borax Rutil glaze

XX16 – 600 °C – Melts well, chocolate as thick, light brown as thin, both thin and thick layers work well.

3 part Borax

3 part Sodium bicarbonate (Soda Ash/Baking Soda)

1 part Lithium Carbonate

1 part Rutil

1 part Kaolin

3 part Quarts

1/2 part Yellow iron oxide

Tin oxide white glaze

XX17 – 600 °C – It is not successful as a white covering glaze, but it does melt! Maybe Borax maks this uneven. To the right is the same glaze but ended up a little out of the hot flame-zone; it is so dry it can be washed off.

4 part Sodium bicarbonate (Soda Ash/Baking Soda)

2 part Borax

1 part Tin oxide

1 part Kaolin

5 part Quarts

Sand color glossy glaze

XX18 – 600 °C – Melted partly in the hottest flames, with too little fluxing agents. Interesting to see that it can melt without Lithium.

3 part Borax

2 part Sodium Carbonate (baking soda)

1 part Talc

1 part Feldspar

5 part Quarts

1 part Kaolin

1/2 part Yellow iron oxide

Vine-red/brown – largely unmelted glaze

XX19 – 600 °C – It is Largely unmelted, but triple the flux amount could get interesting results.

2 part Borax

1 part Sodium Carbonate (baking soda)

1 part Aluminium oxide

5 part Quarts

1 part Kaolin

1/4 part Copper carbonate

Untested – Potassium glaze

XX20 – 600 °C – not started to test with Potassium.

3 part Potassium

2 part Sodium Carbonate (baking soda)

2 part Borax

3 part Quarts

1 part Kaolin

1/4 part Copper carbonate

Dry Lithium Base glaze

X21 – 600 °C – Interesting. I can’t answer why it has green color spots.

My version of Jennifer Harnetty's cone 010 900 °C glaze (300 °C lower):

2 part Lithium Carbonate

1 part Kaolin

4 part Quarts

1/2 part Bentonite

1/4 part Copper carbonate

I found this low-temperature glaze by Jennifer Harnetty

27.5% - Lithium Carbonate

15.5% - Tile 6 Kaolin

54.0 - Silica/Flint/Quarts

3.0% - Bentonite

100% Tot

Boric Acid glaze – too dry

XX22 – 600 °C – Too dry, not melted, did it flux Quarts at all? By scrubbing my finger on the surface, small crumbs are falling off; I can even peel off flakes in some places. Not what I hoped for, but the coloration is interesting.

3 part Boric Acid

3 part Quarts

1 part Kaolin

1/4 part Copper carbonate

The start of a volcanic glaze? Boric Acid

XX23 – 600 °C – The start of a volcanic glaze? Good melt! The coloration is a bit boring, and the surface has small pinholes. Maybe it needs to hold the maximum temperature a bit longer?

|  |

3 part Boric Acid

2 part Sodium Carbonate (American baking soda)

3 part Quarts

1 part Kaolin

1/4 part Copper carbonate

Boric Acid glaze – unmelted

XX24 – 600 °C – Unmelted, too dry, by scrubbing my finger on the surface, small crumbs are falling off, too much Quarts?

3 part Boric Acid

2 part Borax

1 part Lithium Carbonate

5 part Quarts

1 part Kaolin

1/4 part Copper carbonate

Boric Acid melted glaze with surface variations

XX25 – 600 °C – I like this glaze; in the hottest parts, the glaze melted to a nice glossy surface without cracks. On the other side of the ceramics, the glaze is semi-glossy, but it’s a melted and hard surface.

2 part Boric Acid

2 part Borax

2 part Gersley Borate

2 part Sodium Carbonate (baking soda)

5 part Quarts

1 part Kaolin

1/4 part Copper carbonate

Untested – Boric Acid glaze

XX26 – 600 °C – hhh

8 part Boric Acid

2 part Quarts

1 part Kaolin

1/2 part Yellow iron oxide

Untested – Boric Acid glaze

XX27 – 600 °C – hhh

8 part Boric Acid

2 part Sodium Carbonate (baking soda)

1 part Strontium Carbonate

2 part Quarts

1 part Kaolin

1/2 part Yellow iron oxide

End of testing (for now).

Glaze Fire Ceramic In The Campfire

Low-temperature melting fluxes:

Start to flux:

723°C - Lithium Carbonate

~750°C - Borax (Sodium Borate)

~750°C - Boric Acid (do not contain Sodium)

891°C - Potassium Carbonate (Salt of tartar)

~800°C - Sodium Carbonate/Bicarbonate (Soda Ash/Baking Soda)

(pure Baking Soda is only Sodium Bicarbonate (NaHCO₃), while Baking Powder is not pure baking soda).

I desided to leave Lead out of the testing do to health conserns, same to Fluorides and Phosphorus materials; bot can produce hazardousgaseswhen heated.

~800–900°C - Lead oxide (PbO)

~750-900°C - Cryolite (Na₃AlF₆) fluoride-based flux

~700-900°C - Calcium Fluoride (Fluorspar) (CaF₂)

contributes to eutectic melting

Extreme Low-Fire glazes – Glaze Fire Ceramic In The Campfire.

Conclusion:

Ceramic glazes can melt at extremely low temperatures, many hundred degrees Celsius lower than most potters’ work. Several melting agents can, by themselves or in combination with other melting agents, make Quarts melt and form a glaze around 600 degrees Celsius. There seems to be a variety of visual and aesthetic alternatives even for extremely low-fired glazes, though the high percentage of low-temperature flux needed in the receipt is a limitation. It seems like a combination of several fluxes is the best way to achieve the desired melting behavior in a low fire glaze.

In the list above, it seems like the earliest melts happen at 723°C, but does a campfire reach 723°C? I find it a bit hard to believe, directly in the flames maybe, but the flames dance around. I have measured it to an absolute maximum at 600 – 650°C.

1. Maybe some melting starts at a lower temperature than in this list, or:

2. Direct flame can locally, and for a short time heat the glaze enough to start melting.

Here, I continue to develop campfire glazes based on the experience from this page:

strong-melt-for-low-fire-ceramic-glazes/

Glaze fire ceramic in the campfire:

Tested with these low-fire melting agents:

Borax (Sodium Borate, Na₂B₄O₇·10H₂O)

Decomposes into Boron Oxide and Sodium Oxide. and come not as powder but small 0,5 mm balls, I give it a round in the mortar to make powder of them. Too much Borax makes a glaze feel like brush-painting with sand. When Borax is heated, it forms “crystal balls”, that develop out of the glaze surface and start “rolling off” the glaze: The Borax balls finally melt back in the glaze when hot enough. But the percentage of Borax you put in the receipt can be higher in the bottom of a cup than what’s left on the wall of the cup.

Boric Acid (H₃BO₃)

Quartz requires strong fluxing action, and Boric Acid alone is not highly effective at lowering its melting point. Around 500–600°C: Boric Acid fully decomposes into Boron Oxide (B₂O₃). So, when Borax seems to melt better at low temperatures, it’s because Sodium Oxide is a stronger flux, though it needs a higher melting temperature: Sodium Oxide actively lowers the melting point of silica much earlier than boric acid, making Borax a more effective low-fire flux.

Lithium Carbonate (Li₂CO₃)

By far the earliest melter, but it is also a rare and expensive metal. I like to work with cheap, accessible “everywhere” materials, so I am reducing the amount where possible or preferably use nothing. Lithium is an important low-fire flux, and there are not too many to choose between.

Sodium Carbonate (Soda Ash, Na₂CO₃)

Cheap everyday compound (I just love that). Behavior is quite different from borax or boric acid. Is the component used in Soda Firing; and sprayed into the kiln to create a soda glaze. Sodium Carbonate stays mostly in the glaze at low temperatures. At temperatures above ~1000°C–1100°C, Sodium Carbonate that’s pre-mixed into a glaze will also start to vaporize.

Potassium Carbonate (Salt of Tartar, K₂CO₃)

Also known as “Salt of tartar”, it got the highest fluxing temperature in this test. I have not tested it yet since it’s quite caustic, and I need a better mask.

Glaze Fire Ceramic In The Campfire

Not tested these low-fire melting agents:

| 1. Lead. 2. Fluoride Compounds (e.g., Calcium Fluoride, CaF₂): Properties: Fluorides act as powerful fluxes and can lower the melting point of silica. Melting Range: Effective in the 700–800°C range. Use: Used in some low-fire glazes and enamels. Considerations: It can release toxic fumes during firing, so proper ventilation is required. 3. Phosphorus Compounds (e.g., Bone Ash, Calcium Phosphate): Properties: Phosphorus can act as a flux in combination with silica. Melting Range: Effective in the 700–800°C range. Use: Used in some low-fire glazes and specialty glass formulations. Considerations: It can affect glaze texture and color. |

Glaze Fire Ceramic In The Campfire

Check out my other glaze-tests here:

Check out how to fire ceramics in a wood stove:

Check here how to make strong pottery vessels in primitive firing:

make-strong-pottery-for-primitive-firing/

Glaze Fire Ceramic In The Campfire – January 2025

Also two links with ideas:

https://ceramicartsnetwork.org/daily/article/Five-Low-Fire-Alkaline-Glaze-Recipes

https://ceramicartsnetwork.org/daily/article/3-Awesome-Low-Fire-Glazes-Perfect-for-Clay-Sculpture

Glaze Fire Ceramic In The Campfire